A genius at work

The relation between theory and practice

The Renaissance man discovers himself protagonist and advocate of unprecedented works never seen before, thanks to his intelligence and his human awareness. He studies the harmony of reality and returns something great, something that can touch the sky. A very strong bond is created between the smallness of man and the immensity he is able to give life to: he seeks innovation within himself to transmit it to the world and to the others.

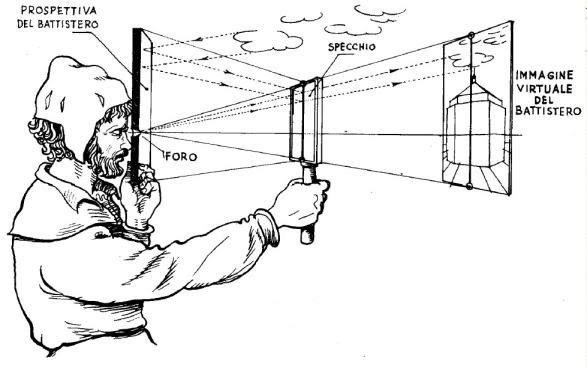

The Perspective Tables of Brunelleschi

Brunelleschi develops a system that allows to return both the depth and the proportions of the figures he’s observing. He “created” what is the principle of perspective, which will be later exposed in the Leon Battista Alberti’s theoretical studies.

The perspective had already been guessed in the Classical period and investigated by Giotto in painting: Brunelleschi explains it from the scientific point of view. We know about the results of his studies thanks to two lost tablets of his we can examine through reconstructive schemes: on square tablet (the side of about 30 cm) he represented the Baptistery of San Giovanni and, to prove that the painting coincided with the real image, he made a hole from which the eye could see the real work.

Using a mirror, looking at the reflected image, he could see his perfect coincidence with reality.

The likelihood was accentuated by the effect created by a silver foil that in the painting covered the area of the sky, in order to obtain a reflected image of the real sky and an exaltation of the illusionistic effect. In this way Brunelleschi realized that, to have a plausible representation of real space, it was necessary to simultaneously adopt a point of view and one of escape.

The orthogonal lines of the composition converged towards this and had to be a guide for the painter in the representation of the elements and their shrinking as they moved away from the observer’s eye.

The Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore by Brunelleschi

The monument symbol of Florence, the Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore contains solutions and teachings that will remain fundamental throughout the Renaissance and will continue to be repeated in the following centuries.

Filippo Brunelleschi, who had already worked at the construction site of the Florentine cathedral in 1409, participated in the new competition of 1418 announced by the Opera del Duomo and the Art of Whool for the construction of the dome.

He first presented a wooden model, winning ex aequo with the goldsmith and architect Lorenzo Ghiberti, later in 1423, managing to solve the technical problems of the construction, Brunelleschi was charged to oversee the whole work. He dedicated all his life: in 1434 the structure was finished, in ’36 the lantern was placed and in ’38 came the four grandstands.

The church of Santa Maria del Fiore was built on a project by Arnolfo di Cambio in 1300 and enlarged by Francesco Talenti in 1360. At the end of the 14th century Giovanni di Lapo Ghini had created the octagonal drum for the erection of the new dome, which would have had a diameter of 41.50 meters: a project unthinkable for the knowledge of the time.

The first problem that Brunelleschi was a technical issue: the enormous coverage would have required scaffolding which started from the ground and wooden ribs to support the dome, up to the arrangement of the keystone but this would have entailed costs and unbearable difficulties.

The Black Death of 1348 had then caused, among the workers, the interruption of the transmission of the practical notions for the construction. It was about to find an aesthetic form that would respond to the existing building and that gave greater visibility to the Dome in relation to all the urban space.

Brunelleschi will be able not only to cope with the technical operations, but also to carry out the design by developing the structure of the building and the scaffolding system and machines able to optimize the efforts.

With him the architect’s role evolves from simple interpreter of a “mechanical art” to true and intellectual, interpreter of a “liberal art”, from master builder to real designer. He was able to effectively organize a construction site capable of responding to the requirements of the different stages of construction.

He creates an extraordinary system with a double lancet dome formed outside by 8 white marbled ribs among which the 8 sails covered with terracotta bricks stretch. The ribs are able to discharge the weight directly on the octagonal drum placed at the base. The smaller and more robust inner dome is entrusted with the task of holding the outer one, to which it provides intermediate supports. This system makes the sails support each other, as well as self-sustaining thanks to the particular arranged bricks, placed in herringbone. Between the two caps runs a gap, that is, a space that, enclosing within itself a connected system of stairs and corridors, reaches the floor on which the lantern is set.

Thanks to the majestic genius of its architect, the dome seems to rise towards the high, swollen and light, so that according to Vasari «the mountains around Fiorenza seem similar to her». Despite the many architectural elements present, Brunelleschi’s “Grande Macchina”, so defined by Michelangelo, is a continuous brickwork and characterized by an effective harmony to make the medieval man understand the greatness and the novelty of a period which will completely change the perspective with which the human gaze and intelligence will look at reality.

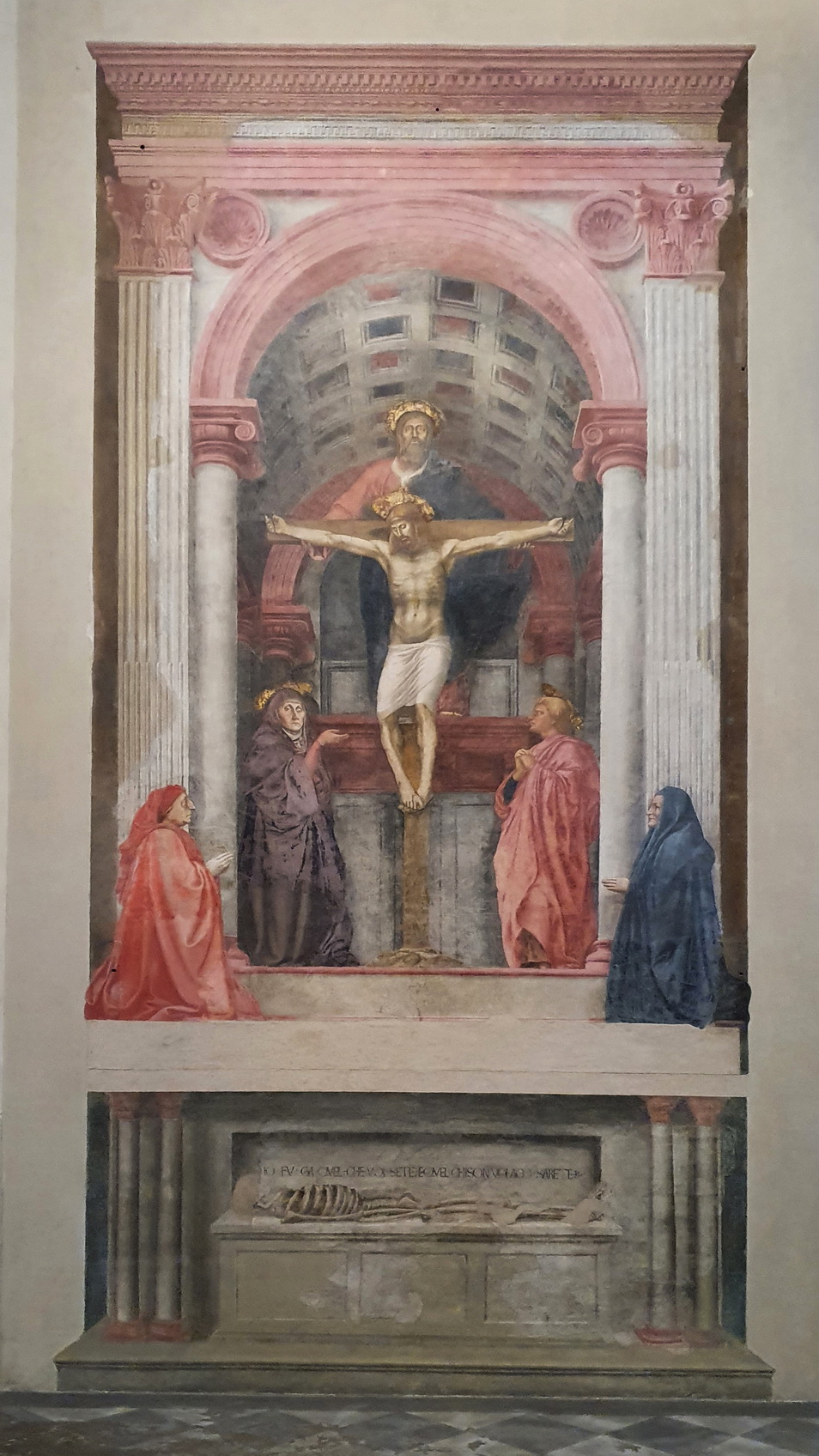

The Trinity of Masaccio

Between 1425 and 1426 Masaccio painted a fresco representing the Trinity in the third span of the left aisle of the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, in Florence.

It is considered one of the most representative paintings of the Italian Renaissance.

A perfect synthesis of painting, sculpture and architecture, the composition is designed in such a way that the chapel is perceived as if it were not only painted, but built, beyond the thickness of the wall.

The narration takes place within a fake painted architecture, in which the reference to the classical world is very strong: from the barrel vault to the lacunari, to the round arches, to the pilasters with Corinthian capital, to the entablature with ornamental medallions. Some art historians have supposed that, given the evident similarity with the contemporary projects of Filippo Brunelleschi, the architect would have taken part in the graphic elaboration, and even in the pictorial drafting of the architectural stage that frames the representation.

Moreover, even in the form of the painted Crucifix, it is possible to see the features of the Christ sculpted by Brunelleschi and kept in Santa Maria Novella as well.

In front of Masaccio’s fresco, the viewer’s gaze is drawn from the bottom upwards in a sequence that progressively leads from the theme of death to eternal salvation. In the foreground there is a sarcophagus, on which is placed a skeleton, bearing the warning I WAS ALREADY WHAT YOU THIRST FOR, AND WHAT I AM YOU ALSO WILL BE, a reflection on the inevitability of death but also on the certainty of the testimony of the Risen Christ.

The figures kneeling in prayer of the clients follow in the background: they invoke the intercession of the saints, Saint John the Evangelist and the Virgin Mary: the latter pointing to Jesus Crucified looks straight towards the faithful who approaches the Mystery of Salvation and becomes a means for his reunion with God.

At the center of the composition we find, finally, the figures of the Trinity, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, arranged according to the iconographic model called “Throne of Grace”, with the Father supporting the body of Christ. This is already the Mystery of the Resurrection of the people of the faithful, gathered in His Church.

NOVÉ ZÁMKY

It is a town in south-western of Slovakia, located along the river Nitra, born with the purpose to respond to the growing Ottoman threat.

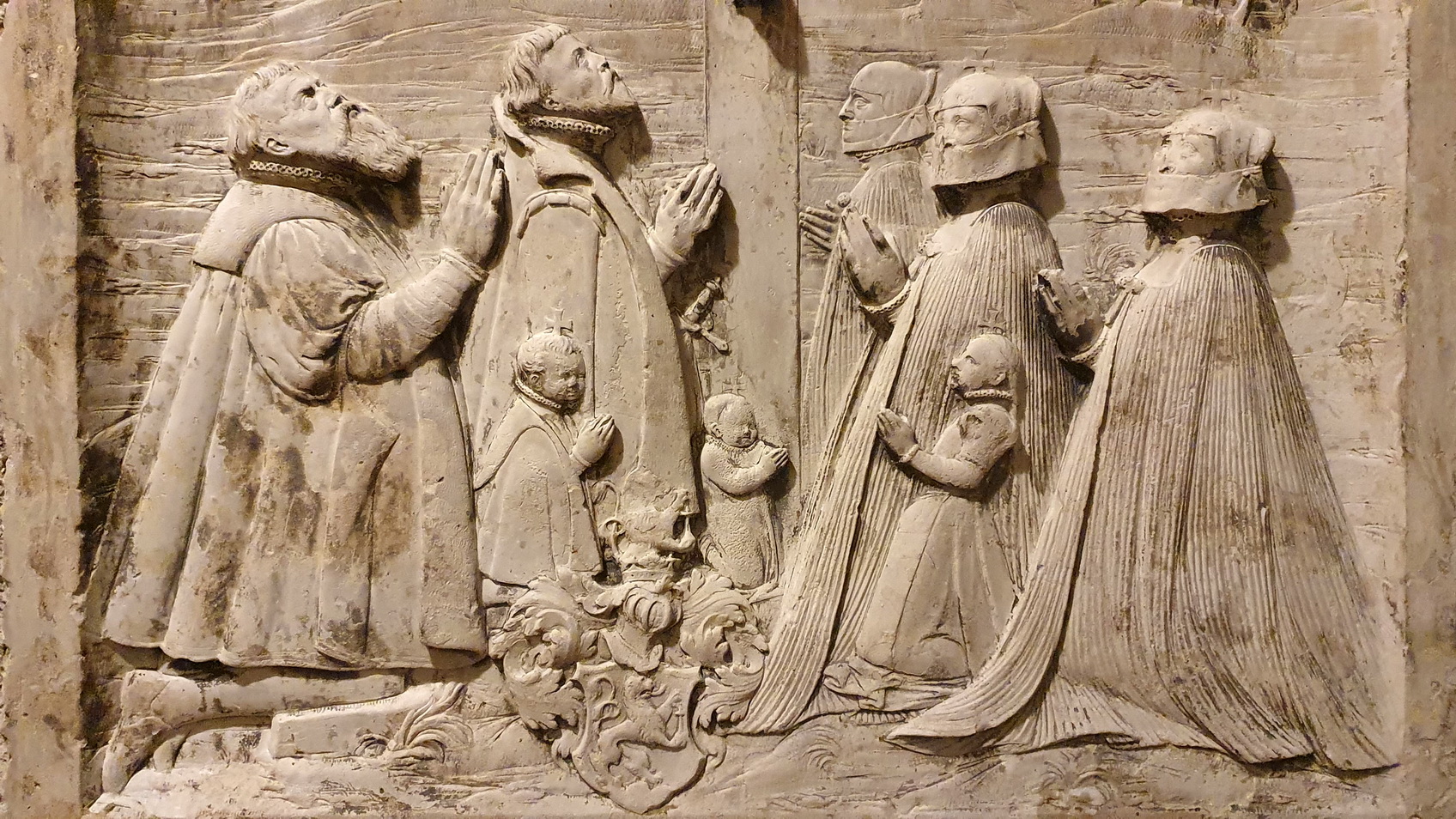

In 1545, at the time of Archbishop Pavol Várdai, the first settlement was born: it was a simple palisade castle with four bastions that, shortly after, Archbishop Nicholas Olah fortified in turn renaming it “Castrum Novum” and, later, Oláhújvár (The new castle of Olah).

At the time it was one of the most modern fortresses in Europe. Between 1576 and 1580 the Kingdom of Hungary redesigned the plan in hexagonal shape, in line with the new construction models that were spreading in Europe.

The city’s second Renaissance fortress was built in marshy terrain on the right bank of the Nitra River between 1573 and 1580. It was designed by the Italian architects Ottavio and Giulio Baldigari as a hexagonal structure, with six bastions at the top and other massive single-nave bastions for artillery, two entrances and a complex tunnel system in the basement.

The walls were surrounded throughout the perimeter by a large moat connected to the Nitra River.

The new fortification became the most modern Renaissance fortress of its time and Nové Zámky the first center for anti-Turkish defense in western Slovakia at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries.

The fall of the fortress of Nové Zámky, conquered during the offensive of the Ottoman Empire on 26 September 1663, was followed by the construction of the fortress of Leopoldov between 1665 and 1669, Designed by the architect L. de Souches and built by the military engineers Ján Melicher and Jan Ungern with a team of 3000 workers from Bavaria and Moravia.

Built in Renaissance style and equipped with the best military defenses of the time, it has a five-pointed star-shaped plan connected by Vellini and surrounded by a large moat. It covers an area of 56 hectares and the defensive walls are 9.5 meters high.

The fortress was converted into a prison in 1855 and received its first prisoners in 1856. She became famous after the February Revolution, when the Czechoslovak communist government imprisoned and liquidated political prisoners.