The passion for the ancient world

and the comparison with the greats of history

The Malatestian temple of Rimini stands on the site of an ancient Franciscan church with a single hall withuout a transept.

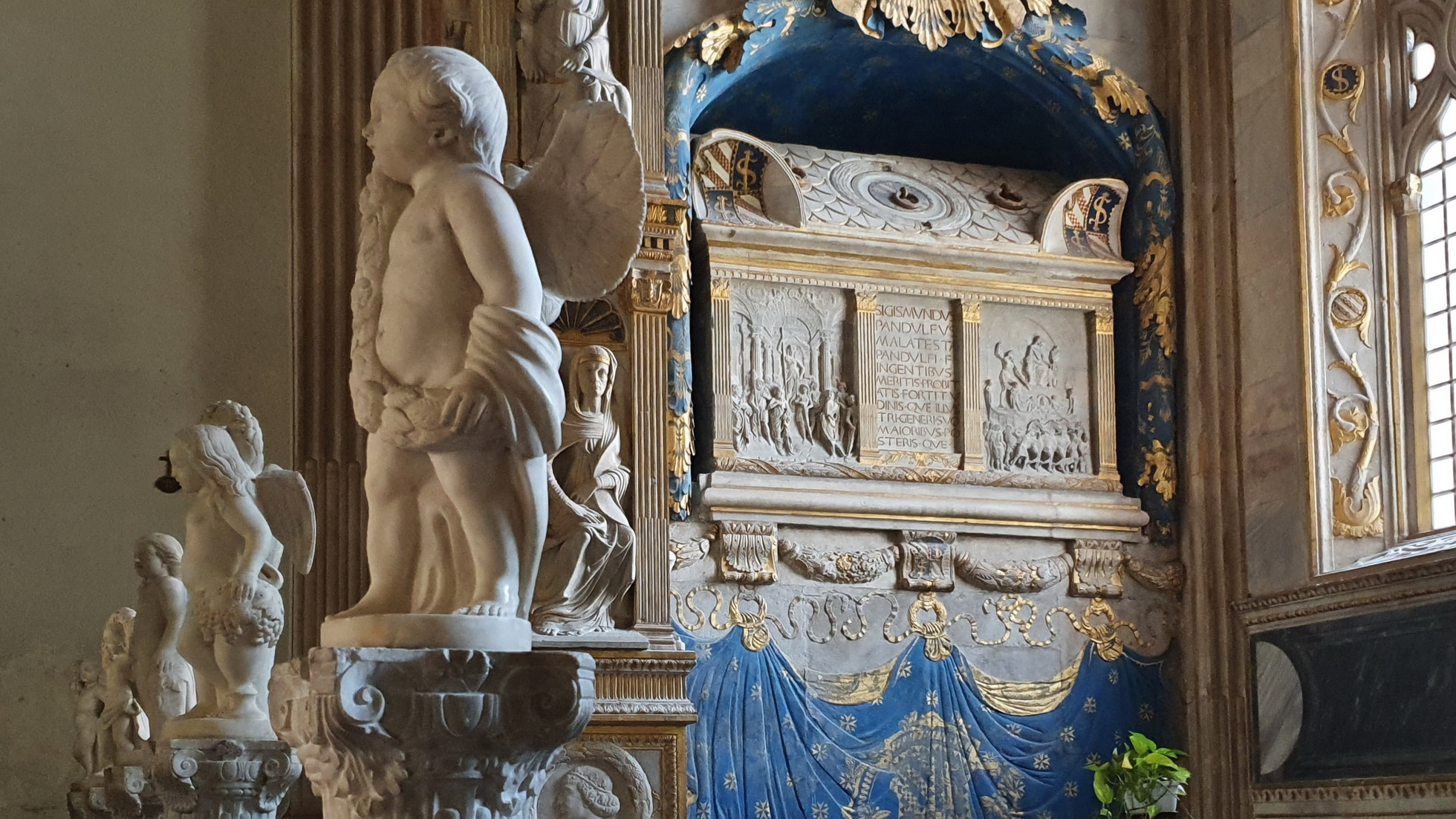

The interior of the building was renovated starting from 1447 under the direction of the architect Matteo de ‘Pasti and the Florentine sculptor Agostino di Duccio by the will of Sigismondo Malatesta, lord of Rimini, who wanted to transform the church into his private mausoleum.

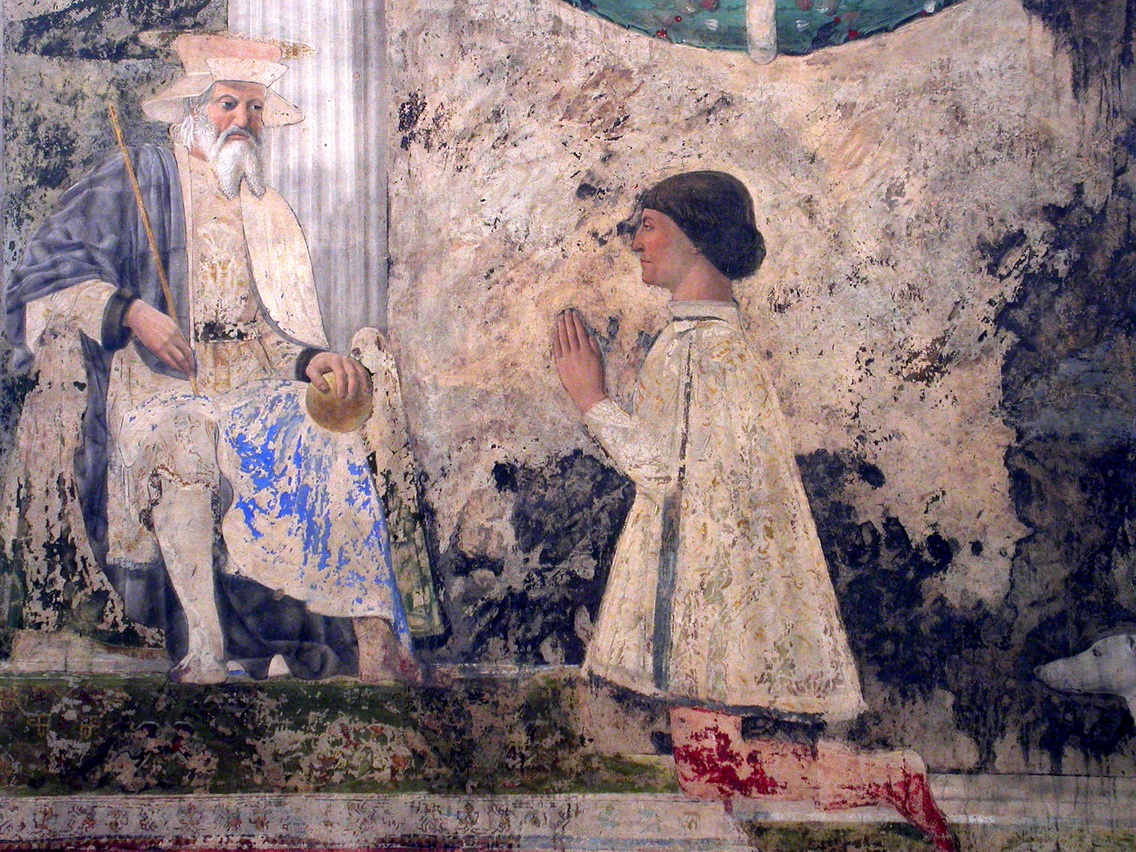

Inside the Temple, in the chapel of San Sigismondo, we find the famous fresco by Piero della Francesca depicting Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta in prayer before Saint Sigismondo, king of the Burgundians and his protector (1451).

The features of the saint and the particular hat (above which there is the halo foreshortened in perspective), recall those of Sigismund of Luxembourg, the emperor who in 1433 invested Malatesta with the title of knight and legitimized his dynastic succession, justifying him the seizure of power over Rimini.

But we want to focus on the external architecture where we find the hand of Leon Battista Albert.

Alberti devised a stone cladding of a very new concept and absolutely independent from the building, as it was taking shape in its internal part (the works started in the early 1950s).

The facade is made up of two clearly divided orders: the first, on a high plinth, is divided by semi-columns that frame three arches, originally designed all equally deep and inspired by Roman imperial architecture, especially the Rimini arch of Augustus ; the upper order is unfinished, but a medal coined by Matteo de ‘Pasti gives us a precise idea.

The facade had to end with a large full-center arch containing a three-light window, flanked by triangular elevations decorated on the top with two volutes, which they connected it to the lower order. Moreover, the following Latin inscription runs on the long frieze of the facade: “SIGISMVNDVS PANDVLFVS MALATESTA PANDVLFI FECIT ANNO GRATIAE MCCCCL”.

The reference to the past is very strong: just look at the facade to realize that the elements in common with the Roman architecture are innumerable and this is the result of the strong push that the Renaissance had given in reconsidering and studying the ancient heritage. It doesn’t appear that Alberti ever visited the construction site where his project, perhaps his first demanding job, was being carried out, although with difficulty.

Indeed, the Rimini building seems to be the verification, the practical experimentation of the theories formulated, or still being formulated in the treatise “De Re Aedificatoria”: both regarding the general conception of the building and its external appearance and the internal decorative structure: for example in the preference given to marble coverings and in the exclusion of fresco cycles, initially included, and for which Piero della Francesca had probably already been in charge.

This choice was made to depart from the late-Gothic tradition and embrace a new constructive and decorative way.The Temple had never been completed due to the untimely death of its lord. It can be defined as a dream, Sigismondo’s interrupted dream, who wanted to make it a stupendous building dedicated “to the everlasting God and the city” and thus give fame and glory to himself and his family and to Alberti, who wanted to make it a monument to exalt the intellectual nobility of man and Humanism. In a way, the Malatesta Temple, due to its formal inconsistencies and its refined intellectualism, as well as its own incompleteness, “materializes” the crisis of humanistic civilization, its internal disagreements, its inability to get out of the closed world of the courts.

Istropolitan Academy

The Istropolitan University, wrongly known as the Istropolitan Academy, is the third university in the Kingdom of Hungary and the first born in the territory of present-day Slovakia. The word “Istropolitan” comes from the ancient Greek name of Bratislava, Istropolis, which means “City of the Danube”. It was founded in 1465 by Pope Paul II (pontificate 1464-1471) at the request of the Hungarian king Mattia Corvino (in office 1458-1490).

Despite its short existence (1465–1491), it occupies a prominent place in Slovak historiography. Within the walls of this university, students, sons of nobles, bourgeois and great merchants, were offered at first the teaching of theology and, subsequently, the courses of study of medicine and art.

This lively reality hosted teachers from Austria and Italy and established itself as one of the most exemplary centers for the dissemination of modern humanistic thought. Among the most prominent personalities we remember Johannes Müller from Königsberg (1436-1476), also known by the pseudonym of “Regiomontano”, German mathematician, astronomer and astrologer, author of De Triangulis omnimodis (one of the first trigonometry treatises completed in 1464 but printed in 1533) and of the Epytoma in Almagesti Ptolemei (critical edition of Ptolemy’s Almagest, printed in 1496).

He had been at the service of Mattia Corvinus from 1467 and had taught here, at the faculty of literature, for about four years.

The Istropolitan University ceased to exist around 1490 after the death of Mattia Corvinus and then resurrected as the “Nova Istropolitan University” which is currently located in a new location in Bratislava.

Today, the old university building trains the young drama students of the Academy of Performing Arts, for this reason it is still incorrectly called “Academy”.

The old institution is still known as one of the seven most important and fascinating monuments in Bratislava to the point that it was used as a symbolic monument of Slovakia in coins.